|

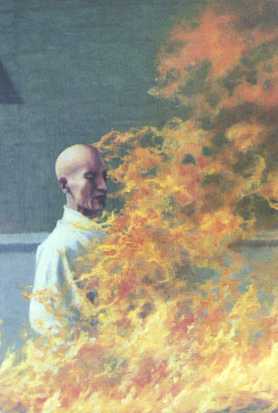

The Unforgettable Fire

I was twelve years old in June of 1963, living in a small town near an airbase in

northern Alberta, Canada; and we, myself and my family that is, had a black and white floor model

television set that was generally the center of our universe. John F. Kennedy was the

illustrious president of the United States, and the Vietnam War was constantly on the news.

So perhaps it was a little more than mere coincidence that I should eventually witness

the shocking airing of the fiery self-immolation of a Vietnamese Buddhist monk in a

busy Saigon intersection. For a rather shallow twelve-year-old going on thirteen, it was both a puzzling

event and a crude awakening to harsh reality. Why would such a gentle soul carry out such

a violent act against his own person? Obviously, all was not right with his world. And was not

his world my world too? Afterall, no man is an island complete unto himself according to

my grade seven English teacher.

Religion and Politics and War

Yes, back there in June of my twelfth year I was spontaneously awakened. Believe me, it

was not the much-desired awakening of an ascetic courting truth and wisdom in an enchanted wood, but

rather the brutal awakening of religion and politics and war. I, and millions of other media-enraptured viewers

around the globe, sat transfixed in absolute horror bearing witness to the self-destruction of

a reverent soul. What little innocence I may have had vanished then and there in the silvery smoke and

flames of our glaring television screen. All of a sudden, there was no glory to war, just

a fathomless sadness about the apparent tragedy of the human condition that to this very day taints my world view.

They say he did not move a finger nor cry out during his self-inflicted cremation. The depiction of the crucifixtion of

Christ doesn't come close to such a ghastly, yet hallowed scene. Why did this unassuming monk choose to end his life in

such a violent manner? What mysterious forces beyond my understanding were at work here? For the first time

in my superficial, barely-adolescent following of the war, I sensed we were not being told the whole truth about what was

going on in Southeast Asia. Gentle beings do not resort to violent measures unless they have

been pushed beyond their limits. Thank God summer holidays were waiting around the corner to

lift me out of the sudden deep depression I found myself in. I remember tearing myself away from the television

screen and looking over to my all-knowing and terribly stoical grandmother for some sort of rational explanation. She only shook her head

and walked back into the kitchen to finish washing the supper dishes. Perhaps the unbearable weight of her silence

was the best response. It seemed the television news soley existed to demostrate just how

powerless we all were when it came to influencing the ways of the world, and afterall,

Vietnam was so very far away. What did one Buddhist monk matter in the overall scheme of things?

The communists had to be stopped in their tracks, even if it meant tolerating a brutally repressive

regime in the south. Well, at least that is what we were led down the garden path to believe.

If you couldn't trust the American government, then who could you trust? How about your

own instincts!

Brave New Millennium

Now that I am older, and hopefully wiser, I can use the Internet and my own cognitive thinking skills to come to a more

informed understanding about that fateful broadcast in June of 1963 when black and white television

forever and a day torched my innocence and tranquility of mind. I now have a computer and a coloured television set that

dish up the news any hour or minute of the day, although my senses have been totally dulled by the

sensationalized reportings of ongoing global atrocities. The Vietnam War has been over and not

done with for a long while, and

there are now other smaller wars going on that grab the limelight from time to time. Innocent

people are still resorting to desperate measures out in the killing streets, and the war propagandists are churning out

their usual hype, lies and doctored video tapes. In the name of this or that religion or political

charter, people are still being tortured and ruthlessly exterminated in this brave new millennium of

ours. Martyrdom is at an all time high, and has undoubtedly become a constant feed for hungry

news departments trying to work their way up in the ratings game. Still, despite all the

depressing news of the present day, the image of the burning monk continues to flash across that

inward eye. I know now that it must be exorcised, that it has become a cancerous growth

requiring the exalted skills of a dedicated surgeon. I shall be that surgeon, ironically with a little help

from the almighty world press via various cyberspace links on the raging information

highway ...

Venerable Thich Quang Duc

I have recently learned that the burning monk's name was Thich Quang Duc. It's not the

sort of name that Westerners would find soothing to the ear, farless pleasing to pronounce. We here in

the West don't warm up too quickly to foreign-sounding names, and Thich Quang Duc's name is

about as foreign and discordant as any name can get; however, his carefully staged

suicide was a media coup which definitely had a resonating influence on future political events

in his country and around the world. The eventual

fall of the blatantly corrupt Diem government was in many ways linked to Buddhist protests

which were popularly supported by the South Vietnamese people. This elderly, astute Buddhist

monk martyred himself in protest against the highly oppressive policies of the American-backed

regime. Three other monks also immolated themselves in the same manner before Diem's

goverment fell. Ngo Dinh Diem and his Vietnamese political allies were powerful

Catholics who tirelessly discriminated against traditional Buddhists. Buddhist monks and

nuns were being detained and tortured by Diem's secret police in the name of a higher

cause, Christianity and the American Way. Buddhists were not allowed to teach or practice their own religion,

and the traditional Buddhist flag of Vietnam was totally banned. The fiery incident at the

busy Saigon intersection was the culmination of repressive events which began earlier in Hue

during May of the same year, 1963. Nine protesting Buddhist monks died in Hue at the hands of

overly aggressive government troops, but Diem turned around and blamed their deaths on the communists. The

idea that the Americans would back such a brutally repressive government is now no longer news. Thich

Quang-Duc was perhaps singularly responsible for turning many American television viewers

against their own government's self-serving involvement in the Vietnam War. Horrifying

television, newspaper and magazine images of the incinerating monk proved to be too powerful for the American war propaganda

machine. It has been noted that Malcolm Browne's Pulitzer prize winning photograph of

Quang-Duc's fiery demise, which ran in the Philadelphia Inquirer on June 12, 1963, was on President

Kennedy's desk the very next morning. Browne's shocking portrait of a Buddhist monk's self-immolation in

the faraway streets of Saigon was profoundly disturbing to Western viewers, who could not

at first fathom the overall intent of such a seemingly senseless act.

Dangerous Times

It's only fair to admit that I was too young to grasp the political significance of

such a desperate act when I witnessed Quang Duc's fiery martyrdom back in June of '63. Yet, even for a young

person more concerned with the ending of another school year, I knew I was watching

a historical event quickly unfolding. I immediately felt great sympathy for the frail monk's

tragic action, and wondered what the world was coming to. I decided then and there that the

war, all war, was wrong, and with the subsequent assassination of President Kennedy, I became very critical

of the American Dream. Would you sit yourself down in the middle of a busy intersection, and

have your friends pour gasoline over you so that you could sacrifice your life for a principle?

I don't think so, as we here in the West are too greedy for life and material things to ever

contemplate self sacrifice for a higher spiritual purpose. Many innocent lives were sacrificed in

Vietnam, and I can recall other shocking television images that did not help America's cause

during those tumultuous years that robbed me and others of our adolescence. Being Canadian,

I never had to worry about being drafted, but thanks to television, the Vietnam conflict was

constant fuel for contemplation. They say every picture tells a story, but certain stories have

to be further told with words, words, words. May the gods bless you, Thich Quang Duc. Yours is truly an unforgettable

fire that keeps on burning in the philosophical mind. Yes, yours is the eternal flame of all great spiritual beings. They say they enshirned your brave and sacred heart.

How ironic in the Christian sense, and yet, how befitting a monk for all seasons. May I live to discover your

buddha nature without ever having to strike a match in the same desperate fashion, for true heroes are

very hard to find. Rest in peace. Om mani padme hum. Let the truth be the guide of man,

for we all, the whole world over, could live with that. Yes, let us stand to your fire.

When one is remembered, one's spirit never dies. Physicians, I have healed myself!

Letter of the Heart Blood

Before he sealed his fate, Thich Quang Duc wrote a letter to the Vietnamese people

imploring them to unite and endlessly strive for the preservation of Buddhism in Vietnam

and around the world. That letter has come to be known as the Letter of the Heart Blood. Ironically, a copy was entrusted to the

care of the government of the day. You see, Quang Duc was no ordinary monk; in 1953, he was appointed

Head of the Rituals Committee of the United Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation, a position

that he held until the time of his self-immolation. No picture can tell the whole story,

but it certainly can awaken an investigative mind in search of nothing but the truth!

Bodhisattva Thich Quang Duc

"The orange-robed monks and the grey-robed nuns appeared to be part of a quiet protest as

they walked slowly down Phan-Dinh-Phung Street in Saigon on a hot June afternoon. Heading

the procession was an automobile filled with monks. At the intersection of Phan-Dinh-Phung

and Le-Van-Duyet streets the priests got out of the car and lifted the hood. It appeared

that they were having engine trouble. The procession parted around the car as if to move on,

but instead the monks and nuns formed a surrounding circle seven and eight deep. Slowly they

began to intone the deep, mournful, resonant rhythm of a sutra. The priests in the auto

walked to the center of the circle and seventy-three-year-old Thich Quang-Duc sat in the

lotus position, a classic Buddhist meditation pose. Nuns began to weep, their sobs breaking

the measure of the chant. A monk removed a five-gallon can of gasoline from the car and

poured it over Quang-Duc, who sat calmly in silence as the gasoline soaked his robes and

wet the asphalt in a small dark pool. Then Thich Quang-Duc, his Buddhist prayer beads in

his right hand, opened a box of matches and struck one. Instantly he was engulfed in a

whoosh of flame and heavy black smoke that partially obscured him from view. The chanting

stopped. The smoke rose and, as the fierce flames brightened, Quang-Duc's face, his shaven

skull and his robes grizzled, then blackened. Amidst the devouring flames his body remained

fixed in meditation".

Above passage from Taking Refuge in L.A.

by Rick Fields and Don Farber.

Quang Duc's sacred heart is kept intact in the

Reserve Bank of Vietnam.

recollections@buddhavision

|